A man walks into a room, finds the files he wants, and strolls out. Done. Objective achieved. The character has an objective: tick. He has a strategy: tick. He completes it: tick. But his actions don’t really encourage those page turns. Why?

The sequence lacks conflict. The character wants something: he goes, does something to get it, and gets it.

But where are the obstacles? What is there to stop him?

If the owner of those files — let’s say, a femme fatale with seduction on her mind — is awaiting his arrival, the man runs into a problem. How does he get the files when this woman wants to get him into bed?

Now, we have conflict. And suddenly, the scene gets a lot more interesting because there’s an objective that becomes difficult to achieve.

And that’s what this article is about: how to create conflict on the page. And by the end of this piece, you should have lots of ideas that will turn your average scene into something unputdownable.

Ready? Don’t write another word until you’ve read this!

What is Conflict?

Conflict takes many forms and is the beating heart of both drama and comedy. I always think that the simplest definition of conflict is “the clashing of objectives.” So, one character wants something, and another does something to stop them or prevent them from getting it.

Conflict isn’t always between characters and it isn’t always an argument. It can be between a character and an environment, for example — more about that in later parts of this series.

Essentially, conflict is born of objective — of the protagonist striving to achieve something that will help them overcome the problem of the world.

Back to the Man Who Wants the Files

If conflict is born of objective, it’s crucial to recognize WHY your character has walked into the room. In well-constructed dramatic writing, a character only ever enters a room if they want something.

Remember, great stories are rarely about someone’s lovely day—great stories occur when a character wants something, and they have trouble getting it. They might want to be alone, escape, hide, or find the files. And it’s our job, as writers, to make that objective as challenging to achieve as possible.

Consider this: we learn more about our characters through the medium of conflict than we do through exposition.

When we force our characters into battle, they display their mettle—we see them strategize when things don’t go their way. Ultimately, conflict allows us to show how our characters are clever (because they overcome obstacles) and tenacious (because they keep trying.

Somebody Wants Something and Has Trouble Getting It

The great dramatist David Mamet defined conflict (and the starting point of all great stories) as:

“Somebody wants something and has trouble getting it.”

And this quote succinctly defines all great stories because:

- Somebody — this gives us a character

- Wants something — they have an objective, something that’s going to get them off their backside and do something to address a problem.

- And has trouble getting it — the conflict.

Think of your favorite movie or novel. Let’s take Raiders of the Lost Ark, but it could easily work with anything else.

Our somebody is Indiana Jones. This is our protagonist — a dashing archeologist who will put himself in grave danger to get what he wants.

Indiana wants something: to find the Ark of the Covenant — a sacred relic containing two tablets confirming the Ten Commandments given to Moses.

But he has trouble getting it — the Nazis are also after the same relic. This means they’ll do whatever they can to stop Indiana from getting to the ark first.

And this particular conflict is heightened (and could be further defined) by the Unity of Opposites.

What is the Unity of Opposites?

The Unity of Opposites is a dramatic construct that locks two (or more) characters into conflict. It creates an unbreakable bond — only one side can win, so they’ll both fight to the death to beat the other to it.

The Unity of Opposites is where one character wants something, but another character also wants that exact same thing. And, if only one party can win, we have a conflict that drives the entire story.

The conflict within Raiders of the Lost Ark is an excellent example of the Unity of Opposites:

- Indiana wants the covenant of the ark.

- The Nazis want the covenant of the ark.

So, we root for Indiana (because he’s our protagonist), and we hope the Nazis will lose (because they’re the antagonists). And the action of the movie becomes a race against time to win the objective.

In its simplest form, Indiana wants something and has trouble getting it.

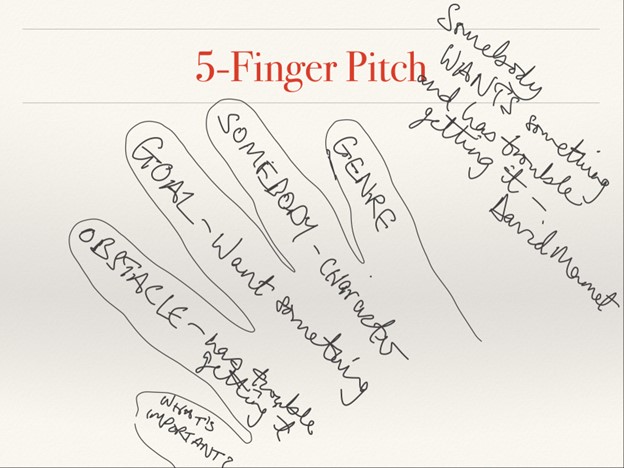

The Five-Finger Pitch

The Five-Finger Pitch is an excellent exercise because it helps you find your someone, identify what they want, and explore the trouble they have getting it.

You do it like this:

- Grab a sheet of paper and a pencil, and draw around your hand.

- In the little finger, note down the genre you’re working with.

- In the ring finger, note down the name of your character. And perhaps something that helps define them, such as their job (or their problem).

- In the middle finger, define what they want, their goal. It’s essential to understand the problem of the world because their objective is typically what they think will overcome and solve the problem.

- In the index finger, think of the problems they face in getting what they want, the obstacles.

- In the thumb, jot down what they learn as a result of their quest to pursue their objective and overcome the problem of the world.

You now have the start of a piece of new writing, driven by conflict.

The Problem of the World

It’s difficult to recognize precisely what your character might want until you acknowledge the problem of the world. When we talk about “world” here, we’re talking about the world of your character; not necessarily the world as a global unit.

If you can define the problem of the world for your character, you’ll understand what’s holding them back from self-actualization. And this helps you recognize what they want and how that will help overcome the issues stifling their lives at the story’s start.

For example, in Pride and Prejudice, our protagonist is Jane. The problem of the world is that her parents want to get her married off. But she’s determined only to marry for love; not for convenience.

And this helps us understand her objective — to find someone she truly loves.

Happy Ending vs. Tragedy: How the Problem Manifests

If you’re writing a story with a happy ending (or a positive outcome), show us the protagonist stuck in a world that somehow stifles them. Show us how the world tramples them down. We start here because we then understand the problem — and to achieve actualization, the character must overcome the pressures and issues holding them back at the start of the story.

If you’re writing a tragedy, it’s often helpful to show us a moment of sheer bliss at the novel’s start. Show us what the character will lose because we’ll feel it all the more when it destroys them at the end.

Of course, either way, there’s a problem—in our happy ending, the problem is clear from the start; with our tragic ending, perhaps the problem is lurking around the corner, ready to show itself by your second scene or chapter.

How Conflict Guides the Action

Once you understand how your protagonist’s objective is born of the Problem of the World, your story begins to write itself to some degree. Create moments of tension where the protagonist wants something, and construct obstacles that make it difficult for them to achieve—it’s the most fun you’ll have as a writer.

Going back to that man in the room: he wants the files — it’s your job as the writer to make it as exciting and challenging as possible.

Perhaps there’s no one else in the room, but the owner of the files is on the balcony—the protagonist must remain as silent as possible as they search the room, so put breakable objects in the path of the files.

Maybe the owner of the files is sleeping in the room. And the files are in the suitcase that the sleeper has rested their head upon.

Either way, the protagonist faces conflict because we — as the writer — put obstacles in the way to make our scene or chapter a genuine page-turner.

Harry Wallett is the Founder and Managing Director of Relay Publishing. Combining his entrepreneurial background with a love of great stories, Harry founded Relay in 2013 as a fresh way to create books and for writers to earn a living from their work. Since then, Relay has sold 3+ million copies and worked with 100s of writers on bestselling titles such as Defending Innocence, The Alveria Dragon Akademy Series and Rancher’s Family Christmas.

Harry oversees the creative direction of the company, and works to develop a supportive collaborative environment for the Relay team to thrive within in order to fulfill our mission to create unputdownable books.

Relay Publishing Wants You!

We hope this article has been inspiring, whetting your appetite to construct conflict within the action of your next piece. Conflict can lift a dull moment into something that forces your reader to turn the page.

If you’re a great writer who relishes a challenge, Relay Publishing is looking to work with you! We have many ghostwriting opportunities right now: learn more about us and how we work.

The next article in this series will be about the various roots of conflict, exploring the differences between internal and external conflict and the different ways we can introduce heightened tension into our work.

Thanks for reading!